The Film Route of Bo Hanna

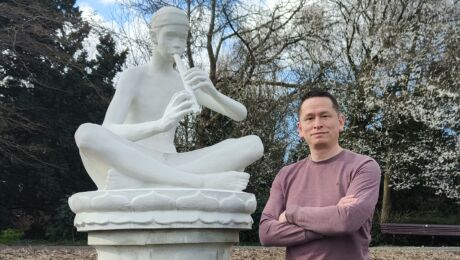

We asked some inspiring tastemakers about their must-sees, so that you dive into the festival with the best tips and some extra inspiration. Today it is the turn of journalist and writer Bo Hanna. 20 March, 2025

In his memoir Baba (2024), Bo Hanna writes about his life-defining experience of being kidnapped by his father. This motivated him to dedicate himself tirelessly to children’s rights, a theme he continuously brings to the forefront as a writer: “Seeing the world from a child’s perspective hopefully encourages you to examine your own role in it and reflect on when you stand up for a child. Films centred on children help us do that.” Bo is currently working on his second book.

Here are his top five picks for Movies that Matter Festival 2025:

-

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Morgan Knibbe

“This film shows how resilient children are and how much they understand. Children speak a different language – a language that requires effort to truly understand. But that effort is often not made, even though they have an incredible amount to say about serious topics.

It is inspiring to see that children, especially outside the West, are very streetwise at a young age. They go through a lot, see a lot, and know how to survive. You may be facing a child, but often they are more mature than we are as adults.” -

Slave Island

Jimmy Hendrickx, Jeremy Kewuan

“Slave Island zooms in on how children become victims of immense injustices in the world. And this is not something from the past – it is still happening in 2025. Child exploitation remains a global issue, to which we are all complicit. Think, for example, of the clothes we wear: you are holding a product that was made by children.”

-

Everything Is Temporary

Juliette Klinke

“This film is set in Myanmar, a country where I have worked and where I was first truly confronted with the complex reality there. I thought: How is it possible that I know nothing about Myanmar while that war has been going on for decades?

Colonialism left the country in a vacuum. When I began to delve into it, it became clear how many countries play a role in this conflict. The geopolitical interests are immense. There is a lot of attention on Israel-Palestine and Ukraine-Russia, but conflicts like the one in Myanmar remain underreported. Still, the geopolitical games there are just as significant, with interests from the West, China, and Russia. Myanmar is a pawn on a much larger chessboard – a game in which we also play a role.” -

The Brink of Dreams

Nada Riyadh, Ayman El Amir

“As someone with an Egyptian background, this film personally touches me. Egypt is a special country. What stands out to me when I am there is how resilient, determined, and intelligent the younger generation is. They inspire me immensely.

They have seen up close what it means to live in a country where a coup has taken place, where major geopolitical interests are at play, where press freedom is restricted, and where strict religious and cultural norms exist. Yet, they resist all of that, with a deep love for their country and a profound understanding. That moves me, because I could have grown up there too.

I am amazed time and time again – not because I underestimate this generation, but because they have had fewer opportunities. Less education, fewer resources, and yet they have made such tremendous progress on their own. That deserves all the respect. I had those privileges, and because of that, I feel the responsibility to use my voice to amplify theirs.

The Egyptian government is increasingly focused on women's rights and campaigns against things like female genital mutilation. You can see that there is a will to bring about change. Women are taking to the streets for their rights, and that has an impact.

A few years ago, a man shot a girl in broad daylight for honor-based reasons. People flooded the streets in response. The government reacted by saying: If you treat women like this in our country, you will receive the harshest possible punishment. This was a powerful signal – a clear message that this will no longer be tolerated.

Women in Egypt have incredible courage. This also involves my grandmother and my mother, who lived their lives within certain religious and societal norms, and within those confines, they found their own way.” -

Yintah

Jennifer Wickham, Brenda Michell, Michael Toledano

“Yintah seems to me like a beautiful film. The subject of indigenous peoples in the Americas deeply touches me. This theme is so relevant – not just in the United States and Canada, but in all areas where Europeans have settled. Now some are calling for borders to be closed: Europeans can go anywhere, but no one is allowed to come in the other direction. In Cape Verde and West Africa, people are drowning in the sea on their way to the Canary Islands because Europe has overfished the waters there, and they no longer have the resources to survive.

The original communities remind us that people have always sought shelter. Why should that be any different now? They show that it can be different – and that is very admirable. They continue to peacefully fight for their land, with respect for nature, because it's not about controlling land, but about protecting nature. Their stories deserve a louder voice in this world.

The film also touches on the global issue of fossil energy and exploitation. Countless countries are still being exploited. This is not only happening in America, but also in Southeast Asia, where islands are being bought up and the local population is being displaced.

It raises an important question: when you arrive somewhere, how much respect do you have for the people who are already living there? Do you come to take something, make money, and destroy everything? Or do you come to truly be there?

There is a lot of misery, but what gives me hope is the growing global solidarity. The resistance of the Māori is not separate from the resistance in Israel and Palestine. If you zoom out, you see that power structures everywhere work according to the same principles.

The West talks about human rights, but when it comes down to it, not all rights seem to be valued equally. This raises questions about institutions like the United Nations and the International Court of Justice. To what extent do they still function in this day and age? They were established after World War II with the best intentions, but how do they operate in today's world?”